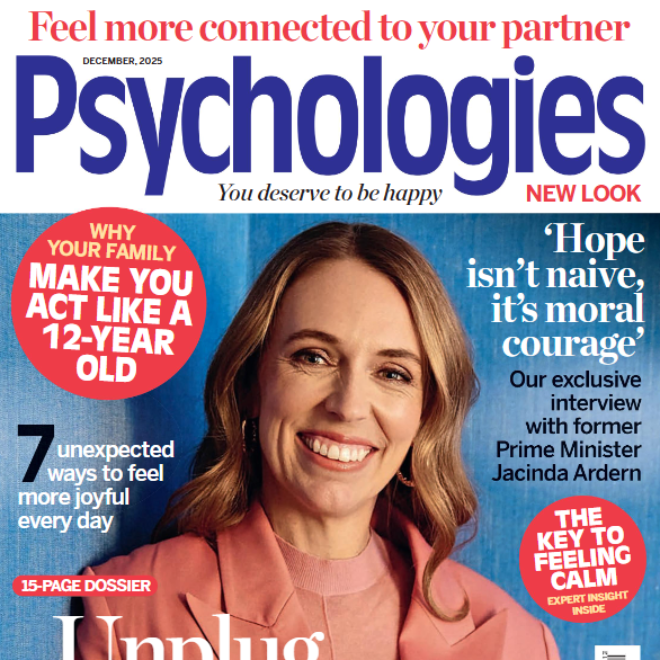

Jacinda Ardern: ‘Hope isn’t naïve. It’s moral courage.’

Editor-in-Chief Sally Saunders sat down with former Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern, to talk about the power of hope, her time in office, and more.

When the Rt Hon Dame Jacinda Ardern sits down to talk about the film that charts her time as Prime Minister of New Zealand, her first words are not political but emotional. ‘I’ve only seen it once,’ she says quietly. ‘Because it’s so accurate — and so intimate — it takes me right back there.’

It’s a revealing admission. Many politicians might watch a documentary about their own life with a certain pride, or at least curiosity. But Ardern, now 45, is not ‘many politicians’.

Her sensitivity — that same quality that made her such a different kind of leader — runs deep. ‘It’s not that I don’t wish to go back,’ she explains, ‘in amongst the tough times, there were also light moments, and there is joy in the memories as well. But there were also some incredibly difficult parts.’

That complexity — light and dark, strength and fragility — defines her.

Capturing a life, unplanned

The film began as an almost accidental project. Her husband, broadcaster Clarke Gayford, had long been in the business of ‘capturing moments in time’.

When Ardern unexpectedly became Labour Party leader in 2017 — only seven weeks before a General Election, and just five months after becoming deputy leader — he suggested filming the journey, ‘not with a particular purpose in mind,’ she recalls, ‘but just because he thought, who knows what we might be part of.’

The result was hours upon hours of behind-the-scenes footage: an intimate record of a woman who never planned to lead a nation, yet did so through one of the most turbulent periods in its history — terror attacks, a volcanic eruption, and a global pandemic. ‘I’ve never been a career-plan kind of person,’ she says with a wry smile.

‘I’m a planner — I love a big wall calendar and colour-coded pens — but I never had a five-year plan. I wanted to do something useful. But I didn’t want to be the leader. I saw how hard it was.’

It’s a startling confession, made without irony. Her reluctance, it turns out, was not a lack of ambition but a profound understanding of the emotional cost of power. ‘All of the ambition I had was about the team,’ she explains. ‘I wanted to be good at my job, to make a difference. But I didn’t think I had the character traits or competency for that top job.’

She pauses, then adds: ‘That was imposter syndrome. I’ve had it all my life.’

The useful side of doubt

When Ardern talks about imposter syndrome, it isn’t the fashionable kind that gets tossed around on social media. For her, it’s a daily dialogue between two inner voices.

‘There was always one that said, “You can’t do it,” and another that said, “But you have to.’’ That ‘you have to’ became her anchor — not ego, but duty.

‘The motivation was different. It wasn’t, “Yes, you can, you’re amazing.” It was, “There are other people relying on you, and therefore you can.” So you park the self-doubt, you compartmentalise it, and you get on with it.’

From a psychological point of view, it’s a fascinating inversion: self-doubt transformed into service, insecurity into empathy. ‘The traits of imposter syndrome are things I actually used in leadership,’ she reflects.

‘It made me prepare more, listen more, bring humility to decision-making. I surrounded myself with experts, and then, because of that process, I could be decisive. That’s a good thing.’ Her style — cautious, collaborative, unshowy — confounded global expectations of political power. It also redefined what strength could look like.

Leadership without ego

When Ardern became Prime Minister at 37, she was the world’s youngest female head of government. A few weeks later, she discovered she was pregnant. The news was, as she puts it, ‘a surprise’. She laughs when she recalls the reactions.

‘I remember feeling like I needed to explain myself — how could you possibly become Prime Minister and then immediately go on maternity leave? It felt like bad planning!’

Behind that humour is honesty. She had undergone unsuccessful rounds of IVF before conceiving naturally, unexpectedly. ‘At the time, it would have been an overshare to talk about that,’ she says. ‘But I still felt like I owed people an explanation. Like what I was doing was somehow unreasonable.’

Ardern became only the second woman in the world to give birth in office, after Pakistan’s Benazir Bhutto. Her maternity leave lasted six weeks. ‘I remember picking that number out of thin air,’ she says. ‘I thought, well, if I have a C-section, I’ll probably need six weeks to recover.’ Her decisions were always pragmatic, rooted in fairness.

‘I remember thinking, I’m privileged — I’ll still be on my full salary. So I donated that to Plunket, the national child health charity.’ She smiles, remembering the delicate balance of those years: running a country, breastfeeding, and trying to be home for bedtime.

‘I didn’t want to look back and think, I wish I’d done that differently. So I set one rule: get home for bedtime. Even if I had to go back to work after, or sit up reading. Consistency felt like normality.’

Partnership, not perfection

In a world obsessed with gender roles, Ardern and Gayford’s partnership still feels quietly revolutionary. ‘He was the primary caregiver,’ she says simply. ‘He enjoyed it, and he was happy to own that title.’

Their domestic life sounds refreshingly ordinary: ‘He’s the dishwasher guy; I’m the meal planner,’ she laughs. ‘We have our different roles. We’re a team.’ When she talks about family, her tone softens.

‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful,’ she muses, ‘if families could make those decisions — who works, who stays home — without judgement? Without it making the mother neglectful or the father less masculine?’

For Ardern, feminism is lived, not declared. ‘People talk about kindness in politics, or empathy, and they often call it “feminine” leadership. I hope it’s not gendered,’ she says. ‘We should expect those qualities in all leaders, regardless of gender. And women shouldn’t feel they have to replicate anyone else’s version of leadership to be legitimate.’

Carrying the weight

The period between 2017 and 2023, when Ardern decided to step down, was a turbulent time for New Zealand. The Christchurch terror attack, in which 51 people at a mosque were killed, all while being live-streamed.

White Island, an unexpected volcanic eruption which took 22 lives. Then, of course, Covid-19. Each event tested her in ways few leaders face in a lifetime. Watching it all replayed on film, she says, ‘takes me right back there.’

Her action in each case was swift and decisive. When Covid hit, she introduced some of the strictest border controls in the world. ‘There was no version of managing that pandemic that was cost-free,’ she reflects. ‘Everyone paid a price, in different ways. You just had to decide which path to take and who would bear the brunt.’

Her tone is measured but grave. ‘When the consequences of your decisions might be life or death, you do carry that weight. Rightly or wrongly, I felt that level of responsibility.’ The toll on her was immense, though she downplays it. ‘I don’t think I should paper over it — it was hard,’ she admits. ‘But not unbearable. I think if you didn’t feel the weight, you’d be either superhuman or subhuman.’

The cost of compassion

Psychologists often talk about ‘compassion fatigue’ — the exhaustion that comes from constant empathy. Ardern experienced a political version of it. ‘When you govern through tough times, you naturally carry some baggage from it,’ she says. ‘You might even become a flashpoint for people’s anger. I wanted the temperature in politics to stay down. I felt that if I left, maybe that would help.’

When she announced her resignation in early 2023, the world reacted with shock. She framed it simply: ‘I no longer had enough in the tank.’ Looking back, she says quietly, ‘It wasn’t about running away. I just didn’t want to undo the good by overstaying. We’d done a lot — abortion law reform, banning conversion therapy, climate and Indigenous policy — and I wanted those things to last.

‘Sometimes stepping away protects what you’ve built.’ That decision — to stop before the world told her to — may be her most radical act of leadership.

A different kind of courage

After spending much of the last couple of years in the States, she is now based in the UK for a few months, where she lectures at Oxford University, writes, teaches, and continues her work.

She describes this time as ‘busy and eventful, but in a different way.’ Her current fascination is empathy — not as a sentiment, but as a form of moral courage. ‘People think empathy in politics is rare,’ she says. ‘But I think many politicians are empathetic; they’re just operating in systems that punish it.’

The problem, she believes, is binary thinking — the urge to simplify, to take sides, to dehumanise opponents. ‘The moment you fall into binary thinking,’ she warns, ‘is the moment you can dehumanise the person on the other side. And that’s what we’re seeing now.’

Her philosophy echoes that of her lifelong hero, Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton, a hero of her father’s and now hers. ‘He called it moral courage,’ she says. ‘In the most desperate circumstances, he chose optimism. Not naivety — but the strength to hold on to hope. And I think that’s what leadership, and maybe life, demands of us.’

The definition of enough

As our conversation winds down, Ardern reflects on the question that used to haunt her: How will I be remembered? ‘When the Christchurch attack happened,’ she says, ‘a colleague told me, “Prime Minister, this will define you.”

‘And I remember thinking, “Not helpful — but probably true.” And then realising I couldn’t think about that. Because in the end, who decides what defines you? Other people do. Just like no one else will decide if I was a good mother, except my daughter.’

That, perhaps, is the quiet secret of her strength — the willingness to be defined not by status, but by relationship, service, and self-awareness. ‘I used to think I might be remembered as the woman who had a baby in office,’ she smiles. ‘And I thought, well, if that’s it, I just hope people think I did it well.’

What shines through — on film, in conversation, in the steady clarity of her answers — is not perfection but presence. The calm insistence that leadership, like motherhood, is an act of care rather than control.

‘I think hope is a form of courage,’ she says at last. ‘And maybe moral courage is just that — to keep believing things can get better. And to act as if they can.’

Prime Minister, directed by Michelle Walshe & Lindsay Utz, is released in selected cinemas on December 5.