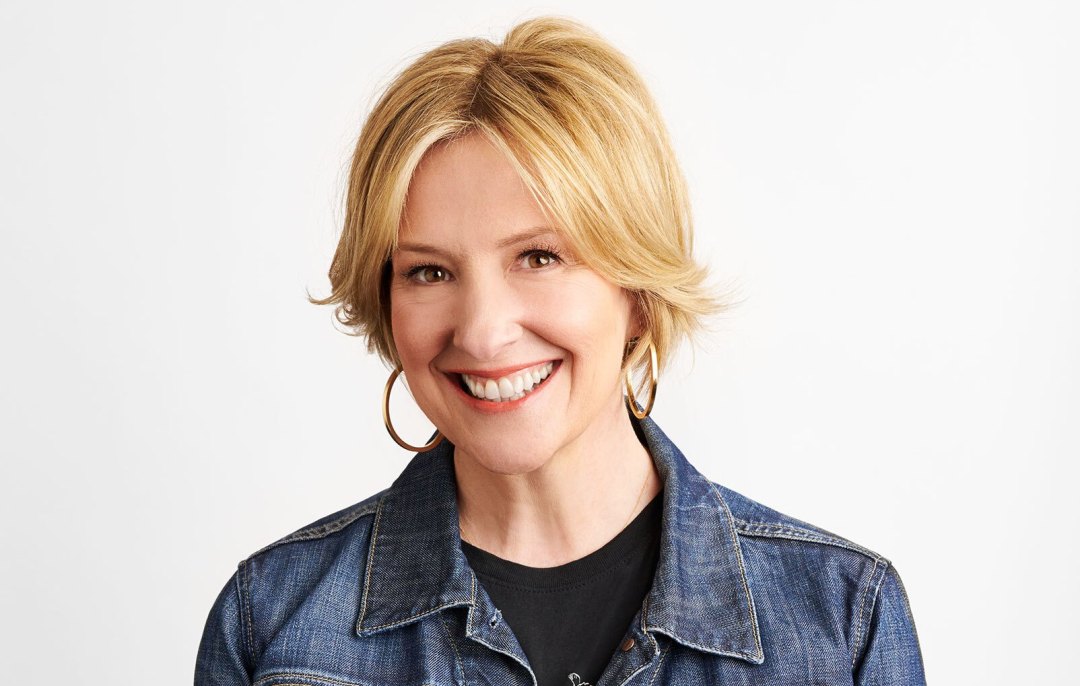

Brené Brown on the curse of comparison and how to avoid it

It’s the curse of modern life: the crush between conformity and competition. The world-renowned author and researcher Brené Brown explores the comparison trap… and how to avoid it

Swimming is the trifecta for me – exercise, meditation and alone time. When I’m swimming laps you can’t call me or talk to me, it’s just me and the black stripe. The only thing that can ruin a swim is when I shift my attention from my lane to what’s happening in the lanes next to me. It’s embarrassing, but if I’m not paying attention, I can catch myself racing the person next to me, or comparing our strokes, or figuring out who has the best workout set. When I go into comparison, I completely lose the meditation and alone time I need. And I once hurt my shoulder trying to race a twenty-something triathlete in the next lane.

I have a picture hanging in my study as a reminder to focus on my journey and to stop checking the lanes next to me. It applies to my time in the pool and everything else – how I parent, my work, my relationships – everything! Researching comparison helped me understand that, like it or not, I’m probably going to check the lanes next to me. But what I do next is up to me. Let’s dive in. (Sorry, I had to.)

Comparison is actually not an emotion, but it drives all sorts of big feelings that can affect our relationships and our self-worth. More often than not, social comparison falls outside of our awareness – we don’t even know we’re doing it. This lack of awareness can lead to us showing up in ways that are hurtful to ourselves and others.

Researchers Jerry Suls, René Martin and Ladd Wheeler explain that ‘comparing the self with others, either intentionally or unintentionally, is a pervasive social phenomenon’, and how we perceive our standings or rankings with these comparisons can affect our self-concept, our level of aspiration, and our feelings of wellbeing. They describe how we use comparison not only to evaluate past and current outcomes, but to predict future prospects. This means significant parts of our lives, including our future, are shaped by comparing ourselves to others.

I’ve collected data on comparison for years, starting with the research that informed my book The Gifts Of Imperfection (Hazelden, £14.99). Guidepost #6 in the list of guideposts for wholehearted living is ‘cultivating creativity and letting go of comparison’. Comparison is a creativity killer, among other things.

Here is my definition of comparison: Comparison is the crush of conformity from one side and competition from the other – it’s trying to simultaneously fit in and stand out. Comparison says, ‘Be like everyone else, but better.’

At first it might seem that conforming and competing are mutually exclusive, but they’re not. When we compare ourselves with others, we are ranking around a specific collection of ‘alike things’. We may compare things like how we parent with families who have totally diff erent values or traditions from ours, but the comparisons that get us really riled up are the ones we make with the folks living next door, or on our child’s football team, or at our school. We don’t compare our house to the mansions across town; we compare our garden to the gardens on our street. I’m not swimming against Katie Ledecky’s times, I’m just interested in the stranger in the lane next to me.

When we compare, we want to be the best or have the best of our group. The comparison mandate becomes this crushing paradox of ‘fit in and stand out!’ It’s not be yourself and respect others for being authentic, it’s ‘fit in, but win’. I want to swim the same workout as you, and beat you at it.

Many researchers talk in terms of upward and downward comparisons. Specifically, Alicia Nortje writes, ‘When we engage in upward social comparison, we compare ourselves to someone who is (perceived to be or performing) better than we are. In contrast, when we engage in downward social comparison, we compare ourselves to someone who is (perceived to be or performing) worse than we are. The direction of the comparison doesn’t guarantee the direction of the outcome. Both types of social comparison can result in negative and positive effects.’

Most of us assume that upward comparisons always leave us feeling ‘not enough’ and downward comparisons make us feel ‘better than’. But researcher Frank Fujita writes, ‘Social comparisons can make us happy or unhappy. Upward comparisons can inspire or demoralise us, whereas downward comparisons can make us feel superior or depress us. In general, however, frequent social comparisons are not associated with life satisfaction or the positive emotions of love and joy but are associated with the negative emotions of fear, anger, shame and sadness.’ These are important findings because, regardless of the different outcomes, in the end, comparing ourselves to others leads us to fear, anger, shame and sadness.

Here’s what makes all of this really tough: Many social psychologists consider social comparison something that happens to us.

Fujita writes, ‘From this perspective, when we are presented with another person who is obviously better or worse off, we have no choice but to make a social comparison. It can be hard to hear an extremely intelligent person on the radio, or see an extremely handsome one in the grocery store, or participate on a panel with an expert without engaging in social comparison no matter how much we would like not to (Goethals, 1986, p272). Even if we do not choose whether or not to make a comparison, we can choose whether or not to let that comparison affect our mood or self-perceptions.’

Whenever I find myself in comparison mode, I think back to an Unlocking Us podcast conversation that I had with my friend, Scott Sonenshein, about his wonderful book Stretch (HarperCollins, £20). Sonenshein is an organisational psychologist, a researcher and a professor at Rice University. In the book and on the podcast, he talks about the popular comparison cliche ‘the grass is always greener on the other side’ and the idea that people spend a lot of time and money trying to get their grass pristine because they want to outdo their neighbours.

As someone who can fall prey to comparing myself and my life to edited and curated Instagram feeds, I laughed so hard when he told me that due to the physics of how grass grows, when we peer over our fence at our neighbour’s grass, it actually does look greener, even if it is truly the same lushness as our own grass. I mean, does it get better than that? The grass actually does look greener on the other side, but that means nothing comparatively because it’s all perspective.

So the bad news is that our hardwiring makes us default to comparison – it seems to happen to us rather than be our choice.

The good news is that we get to choose how we’re going to let it affect us. If we don’t want this constant automatic ranking to negatively shape our lives, our relationships and our future, we need to stay aware enough to know when it’s happening and what emotions it’s driving. My new strategy is to look at the person in the lane next to me, and say to myself, as if I’m talking to them, ‘Have a great swim.’ That way, I acknowledge the inevitable and make a conscious decision to wish them well, and return to my swim. So far, it’s working pretty well.

This is an extract from Atlas Of The Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection And The Language Of Human Experience by Brené Brown (Vermillion, £20)

Photographs: Randal Ford (main image) and Getty Images