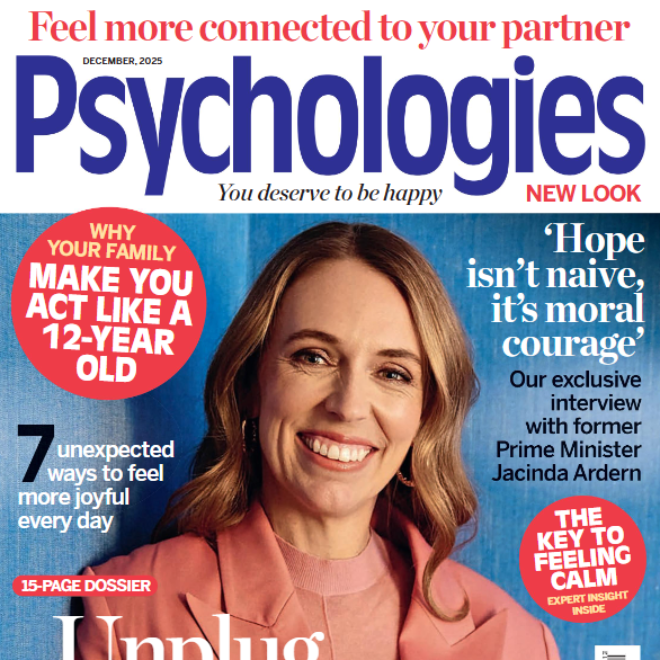

Anna Whitehouse: ‘We’re battery-farmed humans!’

It’s time for a revolution in the workplace, if not for us then for our daughters, says Anna Whitehouse. Here we find out how she’s changing her message to try to get through to businesses, and why she won’t even use the words ‘flexible working’ any more…

She’s spent the last decade working towards equality for ‘people who happen to be parents’, but after a false dawn during the pandemic, Anna Whitehouse says the current situation is worse than ever, with 74,000 women losing their jobs each year for daring to become pregnant — up from 54,000 in 2016.

‘You grow with what you know,’ reflects the social-media star, best-selling writer and radio presenter, also known as Mother Pukka. ‘Had I not experienced a different way with my first child, I would never have questioned the status quo in the UK.’ And what a difference her having that experience has made to thousands upon thousands of women in the UK.

Whitehouse, who last year was named one of the most influential women in Britain, has made it her life’s mission to level the playing field for her daughters and ours.

‘I have three little girls of my own, and I categorically cannot raise them for that same fall that I faced,’ she says ‘So every day I wake up and I look at them and I’m telling them to work hard, to think about what they want to do when they’re older, telling them they can do anything and be anyone. But it’s not truthful. I’m setting them up for a fall.

‘Because categorically, when women have babies, they can’t do anything. We get discriminated against all the time, 74,000 of us every single year.’ She’s referring to the number of women who lose their jobs every year for getting pregnant or for taking maternity leave.

‘Every day I wake up and think: “What can I do to change the landscape for them so they are not pulling together the fragments about postpartum period, wondering who they are and where they’re going.” I would not be here if it wasn’t for them and the abject panic I have within me to try and change this landscape for them, because it isn’t working.’

The landscape was literally different when she had her first daughter, now aged 12, as she was working as a copywriter in the Netherlands at the time.

‘I was living in Amsterdam, where we experienced a completely different way of family life,’ she explains. ‘I had the equivalent of a maternity nurse for 10 days post birth. She was called a kraamzorg, and she would look after me, help me breastfeed, wrap her arms around me so I didn’t have any in laws trying to interfere. I was completely protected in that time.

‘And then when I came to go back to work, my boss wouldn’t let me come back full time. I was paid full time, but had part time hours, because having a child is another job, so they don’t let parents go back full time. I thought that was the norm!’ She had a very rude awakening when she returned to London a couple of years later and had her second daughter.

A new normal

‘Within 24 hours of giving birth, when I still felt like my stitches hadn’t even been stitched up yet, I was wheeled out of hospital in London, all on my own,’ she recalls. ‘And I just remember a disconnect happening, a complete disconnect between myself, and myself as a mother. I almost left my body, I think, in shock.

‘Had I not experienced a different way with my first though, I would never have questioned the status quo in the UK. You just grow with what you know. You accept the path that’s been well trodden before by other mothers. You kind of just go, “Well, this is it.”’

But she couldn’t get over the fact that it could be so different — she had seen that fact with her own eyes. ‘Obviously you pay more taxes in Holland, but they also invest in that postnatal, postpartum period because it saves on antidepressants and anxiety meds later on,’ she says. ‘So they make a saving by protecting a woman in those very vulnerable 10 days postpartum, as the mental-health benefit that support has is incredible.’

It’s a point she returns to time and again: businesses being short sighted and prioritising short-term savings over long-term benefits. And she thinks things are only getting worse. ‘In terms of the working world, we’re going backwards,’ she says.

‘There was a moment when the pandemic bulldozed the way that we worked, and people were more connected to their families. You know, you saw CEOs with pictures their children had drawn in the background. It humanised the workforce in a way that I don’t think we had seen before. And that workforce was more motivated, with fewer sick days, with a higher retention rate.

‘But now you’re seeing in the headlines the PWCs, the Deloittes, the Lord Sugars, the Sir James Dysons, the [Sir] Jacob Rees-Moggs, all saying categorically, “everyone back to the office, five days a week”.

‘Now, that’s bad enough as the evidence shows that hybrid working is far more effective. But the mental-health collateral damage is even worse, as it is actually saying “everyone back in the office, apart from you.” Now, that “you” is anyone with caring responsibilities, anyone with mental-health issues, anybody with disabilities — and frequently that’s mothers. So right now, it’s probably the worst it’s ever been.’

A place at the table

She’s pushing back against the idea that her drive to equalise working policy is simply to benefit ‘mummies who want more time with their babies’.

‘Our fertility rates and our birth rates are at their lowest since 1928, so this isn’t a “nice to have”. It’s not like a little bonus ball for companies to suddenly get on board and go “We should really treat the mummies a little bit better,”’ she says. ‘This is a crisis point in terms of population, as well as crisis point in terms of our own mental health.

‘We’ve celebrated breaking down the nine-to-five model that was born in the Industrial Revolution. But what we’re seeing now is almost smoke and mirrors. There are hardly any jobs on offer or out there that aren’t five days a week in the office.

‘So my driver, my reason to get up in the morning, the reason I quit my job in 2015, was to change the law on flexible working. But it’s not about flexible working any more. I won’t use those words now. It’s about inclusive working. I’m asking businesses: “Are you including Sally at the table? Are you including Anna at the table? Are you including somebody who can’t physically get to the table? Why does it need to be around a physical table in a boardroom? Can’t it be remote? Why can’t it include everybody else who has a relevant voice in this?”’

She’s infuriated that the business world seems oblivious to the benefits this approach could have. ‘It’s a far more business-focused campaign than anyone might think. I care about businesses retaining their best staff. I care about the fact that if you have 30% or more women at the top in your boardroom, you’re going to make more money. I care about the fact there’s fewer sick days when you allow people to work in a hybrid way. I care about retention. I care about the NHS workers who are burning out.

‘This is my wake-up-call for businesses to start to link treating people in a humane way with getting more cold, hard cash. ‘It’s not a favour you’re doing the mothers that you’re currently kicking out of work because they dare to have a baby. When you get rid of us, you’re actively stopping the economy from being boosted by the work that we can contribute. It costs the best part of £28,000 to replace a good employee, so stop being so short sighted.

‘I’m trying to bring the conversation of mental health and profit margin in the same sentence, because the two go hand in hand.’

Battery hens and milking cows

Whitehouse has a rather graphic image she calls on to make her point. ‘If you look at a photo of an office block with people burning the midnight oil, and you look at a picture of chickens in a battery farm, it’s quite uncanny how similar those two scenes are.

‘The battery farm chickens produce really small eggs. The battery farm chickens die sooner. They burn out sooner. They are unhealthy. They’re mentally broken. ‘But the free-range chickens, their eggs are bigger. They live longer, they’re more productive, they’re happier, healthier, able to see their other chickens. It’s maybe a quite binary example, but I think it’s a really relevant one. Do you know what? We’re battery farm humans.

‘The world is not set up for female biology, and so the collateral damage of that is female predominantly mental health. We need more people to stand up and say, “Why are we putting women in windowless rooms to express milk? Why can’t we understand female biology, from periods to menopause?”

‘This structure was built at a time when men went out and earned the bacon and women cooked it. We’re now earning the bacon, raising the children and cooking the bacon. And as a result we are a generation of burnt out, tapped out, drained mothers. And something seismic has to change.’

A lost generation

Growing up in the 1980s, when our mothers’ generation was being encouraged into the workforce while also running the home, plays a big part in the way we view ourselves, says Whitehouse.

‘We saw our mothers be hyper productive, almost incapable of rest and restoration,’ she says. ‘So now we see working and over-productivity as a badge of honour. But where’s the honour in being completely burnt out, disconnected from your body, incapable of looking after yourself, eating discarded crusts from your child’s breakfast, putting yourself so far down that list, because everyone else and everything else is more important than you?

‘Our blueprint was the generation of women who were underpaid or not paid at all, not seen, not recognised, didn’t have the choice of what they did with their purpose, or whether they chose to stay at home or not. It was a lost generation of women.

‘And ours is a generation that’s now breaking all that down, because no, we categorically do not want it all. But are we doing it all? Yes, we are.

‘My cry to arms now is for us to recognise that, and to start prioritising ourselves. We deserve a place at our own table.’

Whitehouse’s new book, Influenced (Orion, £18.99), deals with the highs and lows of social media and is out now.