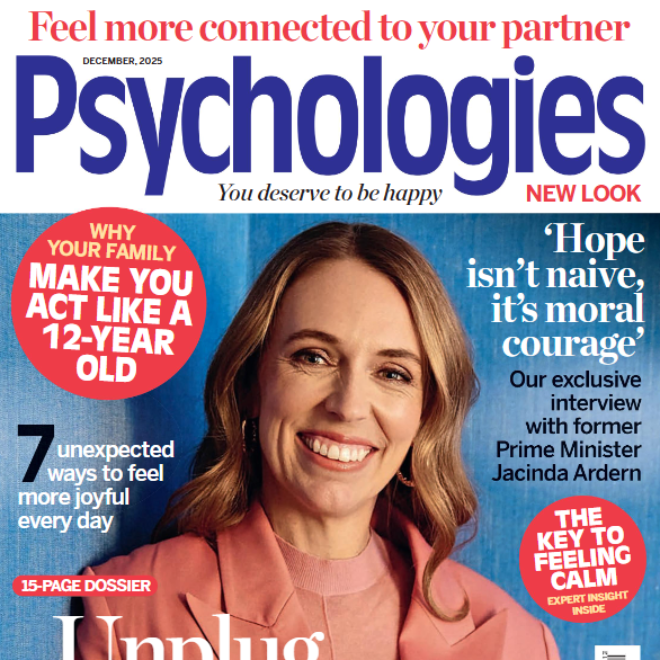

Zoe Blaskey on modern motherhood, guilt, and setting boundaries

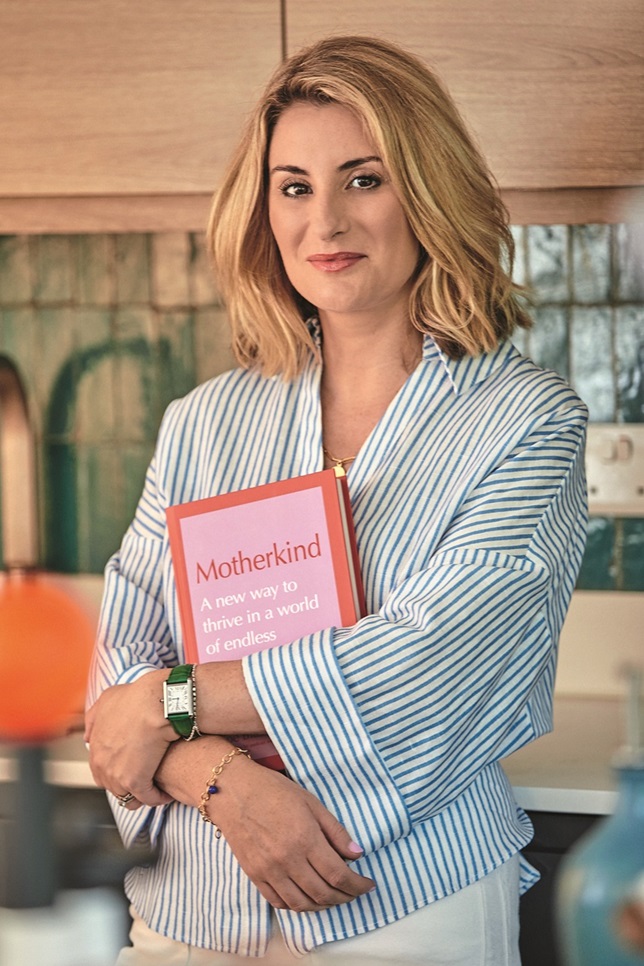

Podcaster and author Zoe Blaskey talks to Psychologies about modern motherhood, endless expectation, and why setting boundaries, not seeking balance, is the key.

Words: Holly Treacy. Images: BobbyNewMan Studio, Rhiannon Duffin

Mum guilt. It’s a relentless shadow that looms over the lives of countless mothers – myself included. In fact, it’s so prevalent it’s been given its own name. It’s no longer just guilt; it’s ‘mum’ guilt. And it can leave us questioning every decision and every moment. According to research carried out by the Peanut app, 97 per cent of mothers say they feel pressure to be everything to everyone. But there is someone shining a light through the fog of motherhood. Her name? Zoe Blaskey. A mum-fluencer, podcaster, and author, Blaskey is on a mission to redefine motherhood and help women take a long exhale as we release ourselves from guilt.

‘There’s so much conversation around guilt,’ she tells me, ‘but what I really wanted to do was help people understand it. The emotional complexities of motherhood are so much and we have so little time to process it; I think we put this guilt on any uncomfortable feeling in motherhood.’

For Blaskey, one of the biggest problems is, when we don’t have a model, we use the wrong solution. ‘What guilt actually is, is when we’ve done something wrong,’ she explains. ‘So we don’t want to get rid of guilt – we need it.’ She recalls a moment recently when she accidentally bashed her daughter Rose’s head on the side of her car seat and she felt really guilty about it: ‘Rightfully so!’ Blaskey says. ‘That shows I’ve got empathy and I’m connected to her. Only psychopaths feel no guilt. So I call this good guilt.’

Good guilt? ‘Say one of your core values is kindness and compassion,’ she continues, ‘and you’ve been screaming and you’re being horrible. You would want that guilt to prompt you into action. But with “mum” guilt, 20 per cent of what we feel is that good guilt, but about 80 per cent of it isn’t guilt at all. You’re not doing anything wrong for being human; for working; for wanting things outside of motherhood.’

Measuring up

So if it’s not guilt we’re feeling, what’s really going on here? Blaskey refers to the solutions around ‘mum guilt’ as ‘tea sips’, rather than big changes, and believes the first big point to understand is that we’re not feeling guilt, it’s tension. ‘I think that motherhood is just one big experience of tension,’ Blaskey says. ‘But we need to accept that if we’re going to make choices to do things that are important to us, there’s always going to be tension.’

So whether that’s saying no to a friend because you want to put the kids to bed, passing up a work opportunity because you want to be closer to your children, or arguing with your partner because you want to advocate for your needs more, there’s always going to be tension. ‘It’s like pulling a rope tight and then learning to drop it,’ Blaskey explains. ‘When I teach mothers this, I physically see them drop their shoulders, too.’

According to Blaskey, the key is to accept that you can’t cut yourself into multiple pieces: ‘You’re going to make the best choice that you can today based on your values, but also knowing that you might regret that choice one day – and that’s okay, too,’ she says.

Blaskey’s second ‘tea sip’ is on standards. ‘So much guilt comes from mums measuring themselves against unrealistic standards,’ says Blaskey. ‘This is what I refer to as the “should scam” in my book, Motherkind.’ These are the unconscious beliefs that Blaskey believes are running our version of motherhood. ‘How many of us saw our mothers growing up in the 1980s and 1990s? They tended to not work as much. They tended to be all joy and florals and secret gin drinkers in the evening!’ she laughs. ‘It was a completely different time. But we’ve absorbed all of that, and it’s those hidden beliefs that drive those standards. I really noticed this when I would be beating myself up for working – but I realised this wasn’t my idea. My idea of motherhood is that I wanted to work. I love my girls seeing me work – I’m a better mum for it.’

So why did she feel guilty for it? ‘I’d internalised the standard that “good” mothers should be fulfilled by motherhood and motherhood alone. As soon as we start to define our own standards, the guilt begins to wash away.’

The third ‘tea sip’ (or big gulp) is looking at the inner critic, or the part of us that is constantly chatting. ‘It’s actually, and I learnt this from Dr Nicole LePera, the inherited critic,’ Blaskey tells me. ‘Does that inner voice sound a lot like your teacher, or your parents? It might be saying things such as, “You’ve done it wrong again,” or “You can’t cope,” or even “Why can all these other mothers feed their baby, but you’re getting anxious about it?” It continues past the newborn phase and you hear phrases such as, “Why can’t you get your child to sleep?”, “Why can’t your toddler use the potty yet?”, “Why is your teenager behaving like this?” We believe it must be our fault. We can get stuck in this loop around everything, not just motherhood.’

For Blaskey, the critic gets loudest the more that we care about something. ‘I’ve never cared for anything more than my girls,’ she shares. According to Blaskey, the moment we notice our critic, we’re 80 per cent there. ‘You can’t change what you’re not aware of,’ she says. ‘If you’re running the belief that you’re not good enough, you will start to notice evidence everywhere that that is true. But something you could start saying to your critic is, “I’m handling everything I need to at this moment.” And if you keep repeating that phrase, you might start to notice evidence that confirms that.’

Sharing the Load

You might think that for someone who has been doing this work for two decades, her inner critic must be well and truly silenced, but Blaskey confesses it is still ever present. ‘Even I’m surprised by that!’ she laughs. In the book, she recommends a technique she uses called ‘First thought, second thought, first action’. ‘I’ve noticed that my first thought around something is usually a negative one, and if I catch it really quickly, I can choose a better second thought. For example: “What kind of a mum puts her kids in summer camp, while she goes to London to follow her dreams?”’ (Blaskey has sent her girls to camp so she can promote her new book.) ‘I can hear that, but then I can choose to think, “I’m proud of myself. I’m showing my girls what it looks like to lean into a passion and career, and to be of service and try to make change in the world.” So then my first action would be getting on the train to come to London!’

Depending on how wide our emotional vocabulary is, we can sometimes mistake some feelings for others, and Blaskey believes this is the case when it comes to guilt. ‘Sometimes, we can absorb other people’s emotions as our own,’ she says. ‘Another mother could question why you are doing something, because they never used to do it that way, and suddenly you feel guilty and question if you’re doing something wrong.’ Blaskey says the best thing to do here is to ask if that is your feeling or someone else’s. She recommends visualising a glass wall between you and them so that the feelings can’t permeate. ‘We want to empathise with people, but we don’t want their feelings to fill our whole bodies and transmute into guilt. From the eye roll from another mum, that tut from the supermarket worker, your partner’s sighs – you can absorb it all and turn it into your guilt.’

‘I think a lot of what we call guilt is actually shame,’ she adds. ‘People will say to me, “I feel so guilty; I’m a terrible mother.” Guilt is about behaviour and shame is about who you are as a person. Brené Brown teaches us that shame dies in the light. So, the best way I’ve found around this is to share what you’re feeling with others. Find a safe person that you trust to share your guilty feelings with – hopefully that person will hear and validate you, and offer you some kind words. If you don’t have that person, you can go into nature, which is amazing at co-regulating us. Even just speaking it out into the air can help to lessen those feelings a bit.’ Blaskey likens guilt to being wrapped up in a rope, but by using these tools, the rope becomes a little bit looser, so you can wriggle out and find freedom.

Perfectly imperfect

Along with guilt often being confused for another feeling, Blaskey believes perfectionism is also misunderstood.

‘People say to me, I’m not a perfectionist because I’m such a mess! But let me tell you, you can be a perfectionist and have an untidy house, be late to every appointment, and not have showered in a week,’ she says. ‘Perfectionism is not about being perfect, it’s about trying to be perfect. Nothing is ever good enough.’ She tells me that this might stem from early childhood, where you may have been praised for success.

‘I liken it to a mirage,’ she says. ‘You’re running towards what you think is the finish line, but the moment you get anywhere near it – you’ve tidied the living room, you’ve made the dinner – the perfectionist will say to you, “But you didn’t meet that work deadline, or respond to that email; you’re a mess – you need more clothes, and look at the state of your kid!” So you will never get to the end of that finish line. And that’s what leads to burnout. It’s like being on a really cruel hamster wheel. You could achieve 100 things in the day, but your perfectionist mindset will wipe away what you’ve done and then give you 100 more tasks.’

Before you get stuck in the guilt trap for indulging in perfectionist ways, try to focus on what you have done. ‘This is about starting in tiny 1 per cent ways,’ Blaskey shares. ‘I am worth sitting down and leaving the dishes; I am worth saying no to my kid who is begging me to play, because I just need five minutes of peace. With every action that we take, we’re either reinforcing an old belief, or we’re creating a new one.’

For Blaskey, the bigger this discomfort, the bigger the pattern is to break, so no matter how tempting it is to fold the washing, or get a few more emails done while your baby naps, she suggests taking a break.

Boundaries not balance

Like most new mothers, I was taught that our postpartum lasts between six weeks and six months. So, imagine my guilt, shame and inner critic when I’m still unravelling more than two years later. But it turns out there is actually a word for the transition into motherhood, and it was coined in 1973 by anthropologist Dana Raphael: matrescence. ‘Is just like adolescence,’ explains Blaskey. ‘We all know that is a period of wild hormones, brain, behaviour and values changes, friendship and identities changes, and it’s a really bumpy time. We give teens a little bit of bandwidth to settle into the new version of themselves.’

Matrescence is exactly the same for mothers. I thought there was something wrong with me – if I’d known about matrescence when I had children, I would know that I was struggling because I was doing it right. ‘What we actually know from matrescence is that the process of figuring yourself out as a mother is seven to ten years,’ she tells me, and she can see me visibly exhale.

‘Matrescence is like a jigsaw puzzle: you go into motherhood and you know yourself, but matrescence is throwing that puzzle up in the air and putting it back together again once you’ve become a mother. So I want people to know, if your jigsaw puzzle is scattered into a million different pieces right now, in a way, you’re doing motherhood right!’ Most new mums will be familiar with the ‘bounce back’ message, and Blaskey believes it is not only unhelpful, but also offensive. ‘We can’t go back to our old selves once we enter motherhood,’ she says. ‘If we think about any other heart-opening, life-altering event – a grief, a death, a divorce – we wouldn’t expect people to bounce back to who they were before this. But we expect it of mothers.’

As women, we’re told we need to fit back into our old life, our old friendships, and our old jeans. ‘We do mothers a huge disservice by telling them they need to be their old selves, with a smile on their face and a baby on the hip,’ she says. ‘It undermines the transformation on every level of what it is like to become a mother. I believe we grow forward, rather than bounce back.’ Like with stress, grief or burnout, self-care is usually the prescribed answer to the pressures of motherhood, but Blaskey has a problem with this: ‘Self-care doesn’t work,’ she says bluntly. ‘You’ll hear people saying they are having a moment of self-care because they are getting their nails done or having a bubble bath.’ For mothers, this feels completely inaccessible, because it takes two things we simply don’t have enough of: time and money.

‘It becomes something else for us to feel guilty about,’ Blaskey says. ‘From a physiological point of view, it doesn’t complete the stress cycle, so it doesn’t actually make us feel that much better. Often, laying in a bath can leave mums feeling more stressed, because they’re left with their thoughts whirring.’ Blaskey suggests something called energy management. ‘When we plug our phone into charge or put petrol in our car, we don’t think “Is this phone worth charging?” No, we think, I have to charge my phone if it wants to keep going. And people are exactly the same. It’s not about whether you’re worthy of taking care of – if you want to continue doing everything that you’re doing, you have to recharge yourself.’

For Blaskey, one of her issues with self-care is that it is so prescriptive. ‘I’ve had mums say to me that they should do yoga, and when I’ve asked if they even like yoga, they’ve said no!’ So Blaskey asks, what is it, when you go through your day, that gives you energy? ‘Is it when you drink a glass of water before you have tea or coffee in the morning? Is it when you play a game with your child and it really makes you laugh? Is it when you take a breath before you transition between meetings? Those are energy givers.’ Like many of us, Blaskey believed for years that what she needed more of was balance. But balance is when all the different elements in your life are all in perfect sync.

‘That’s insane!’, she says. ‘That is never, ever, ever going to happen. One week your child’s going to be ill, and you’re going to have to put all your attention there. The next week, your partner might be made redundant or your sister might have a crisis, and you’re going to have to put all your attention there. Then, you’re going to have a big work deadline and you’re going to have to put your attention there. We are always in this state of flux,’ she shares. ‘And when we’re doing that, we’re not thinking to ourselves, this is really good. I’m leaning into what my life requires of me right now. We’re beating ourselves up for not having any balance.’

So how can we stop this idea of balance? Start thinking about boundaries, instead, Blaskey tells me. ‘Boundaries are the limits that we need in our life to enable us to keep going with everything,’ Blaskey says. ‘Essentially, without boundaries, what we’re saying is we’re limitless. We have limitless time, limitless energy and we have limitless emotional capacity to give. That’s how many mothers that I see are living; as if they are limitless, as if they can just give and give and give and there’ll be no consequence.’ According to Blaskey, we have to get more adept at leaning into whatever requires of us in that moment, but not just piling on these things on top of what we’re already doing. One of the most powerful tools Blaskey writes about in her book is compassionate letter writing. She admits that it will feel super awkward and weird in the beginning, but then it will start to feel amazing, and you will start to soften.

‘It’s the number-one way that I seem to be able to figure out what I really feel,’ she says. And it’s super accessible for mums. ‘It’s free! Who doesn’t have a pen and a pad,’ she laughs. It’s different from straight journalling, because it’s the compassionate piece that is so important. When she starts to give me an example using the words: ‘My darling, Holly, I know that you’re struggling right now. I want you to know that I’m so proud of you…’ I can already feel my heart in my throat.

For Blaskey, so much of the conversation is about how hard motherhood is. ‘There are so many funny memes – we all share them around – but there’s not enough tools. So we need new tools for new times. And that’s what I’ve tried to create with this book. Here is the toolkit that you need to support yourself, and it’s not about how to feed your baby, or how to wean your toddler, or how to potty train. It’s not about any of that. It’s not about parenting. It’s about us.’ Blaskey’s words, both in person, in print and audio, feel like ones of a friend you wish you could be to yourself. It’s not just that she’s compassionate to mothers – she’s on a mission to empower us, too. She’s given us permission to cut ourselves some slack as we lean into our changed selves.

That deep breath we’ve all been holding in? We can finally let it go.

Motherkind: A New Way To Thrive In A World Of Endless Expectations by Zoe Blaskey (HarperCollins,£16.99) is out now.

Find Zoe on Instagram at Instagram.com/zoeblaskey