What imagination taught me about anxiety

A hobby can teach you much more than a new skill...

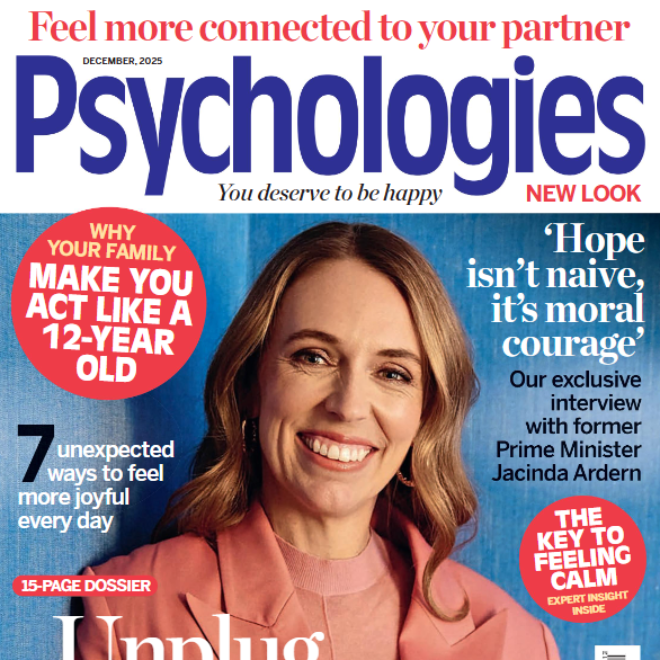

Lucy Lawrie, author of The Last Day I Saw Her, talks about the things she learned about herself when she became a writer.

One day, my three-year-old came to me crying, having discovered a tear under her toy bunny’s arm. I suggested we phone Granny (who can actually sew), but Charlotte fixed me with urgent wide eyes and told me that we would need Invisible Fred. A creeping sensation went through me. Who was Invisible Fred?

I suddenly recalled my own, slightly alarming, imaginary friends, Ux and Timothy, who appeared at the dinner table one day when I was four years old. Lacking in any moral code, they threw vegetables on the floor at mealtimes and scribbled in my Ladybird books. After a year or so, they disappeared as suddenly as they’d arrived.

Children often have a very fluid sense of what is real. As a child, I made sprawling Lego towns inhabited by families of tiny animals, enacting their lives, soap opera-style, over weeks and months. I remember crying for days after leaving my anorak at the beach, worried that it would be cold and lonely.

We know that play is crucial. It helps children to see things from other perspectives – the foundations of empathy. They use it to make sense of themselves and the world around them. Interestingly, at around the same time I began to grow out of playing, I started to experience anxiety as a problem, as something that slowed me down and made life feel di fficult. I suppressed it enough to do some of the things I wanted to – I did well in my exams, went to university, qualified as a lawyer… attended to the serious business of ‘real life’.

Motherhood stopped that life in its tracks. It was the scariest thing that had ever happened to me. I lived on a knife-edge of fear that something might happen to my baby, or to me; nightmare scenarios that always spiralled towards the worst possible unhappy ending. Anxiety had me well and truly in its grip.

It was my six-year-old self that saved me. While still on maternity leave, I stumbled upon a primary school homework book in which I’d written, ‘I want to be an author when I grow up’. I felt for this small person who had reached through the years to speak to me. I started to write because I didn’t want to let her down, with her certainty that she had a voice and stories to tell. Now I see that I was the wobbly one, and she was the one who knew what she was talking about.

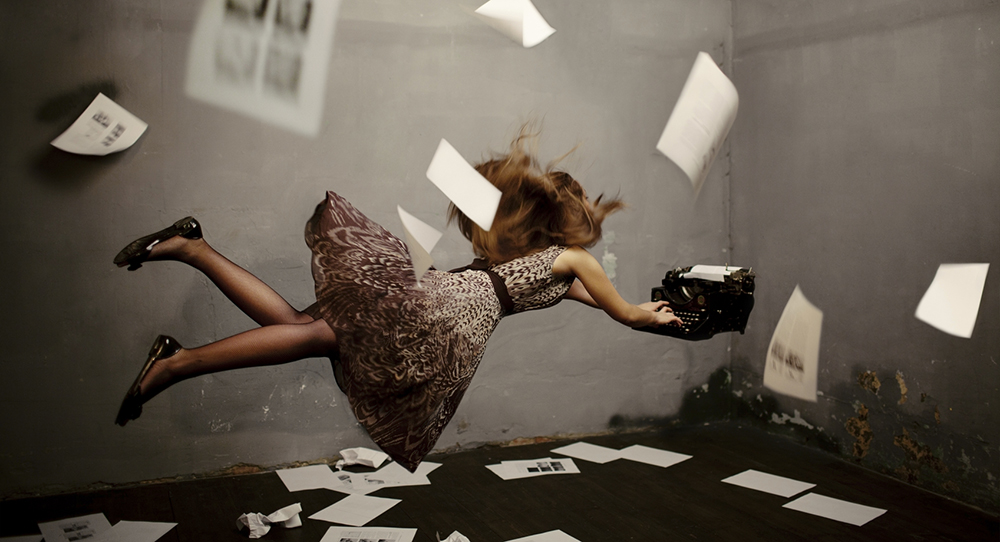

In creating stories, I found my missing link – the ability to play. I did exactly what I’d used to do with my Lego towns – happily sitting down at the end of the day and making my characters act out my stories. I let out the Ux and Timothy spirit that I’d learned to suppress, and allowed mischievousness into my writing. My characters became as real as my erstwhile imaginary friends.

And I discovered that, when I was in creative flow, my anxieties didn’t bother me. My old childhood self, the one who knows how to play, also knows how to let me fly above my fears.

Photograph: iStock