Shelf Help December: Alex Clark on The Hare With Amber Eyes

An epic family history during a turbulent century, Alex Clark explores the themes of the award-winning bestseller from Edmund de Waal

Why do we hand things on from generation to generation? What do those objects mean to us, displaced from their original time and context, separated from their first owners or makers? And what of the things that somehow get lost in transit, that get broken or taken or simply discarded?

Edmund de Waal’s extraordinary family memoir, in which he narrates the story of a collection of wood and ivory carvings that eventually found their way to him, is a powerful exploration of these questions; a meditation on how we can both allow objects to open up the stories of the past for us, and yet still understand their essential nature, before the passing years covered them in layer on layer of history.

The ‘hare with amber eyes’ is one of the 264 Japanese netsuke originally bought in Paris in the 1870s by Charles Ephrussi, a cousin of de Waal’s great-grandfather. These tiny carvings, studded with fragments of horn and amber – among them a snake curled on a lotus leaf, a walnut shell, a naked woman with an octopus, and a mikan orange – were the very epitome of fashionable Paris’s love affair with all things Japanese; its attraction to new styles, new materials, and objects that, rather than being designed to hang on a wall, were meant to be touched.

For Charles, whose involvement in the art world led to his featuring in Renoir’s famous picture Le Déjeuner des Canotiers, the netsuke were a marvellous acquisition; but also one that, at the turn of the century, he was prepared to send to Vienna as a wedding present for his cousin Viktor.

De Waal, an acclaimed ceramicist, was the fifth generation of his family to inherit the netsuke; immediately before him, they were in the loving care of his great-uncle Iggie, who lived for most of his life in Tokyo, thereby returning the carvings to their country of origin.

Among other things, the book is an incredibly moving record of a family’s travels; from Odessa to Europe, where they divided themselves between Paris and Vienna, and from a Vienna torn apart by the predations of the Nazis to Switzerland, Mexico, the USA and – unlikely though it sounds – Tunbridge Wells in Kent.

It is also the story of the rise of the Ephrussi banking dynasty and, through the course of two world wars, its decline; and of the anti-Semitism that plagued the family from smart Paris salons to the arrival of the Gestapo at the Palais Ephrussi, a hideous episode after which the property was declared ‘fully Aryanised’. De Waal’s account of his family’s flight from Vienna – a city in which Jewish men were renamed Israel, Jewish women Sara – is terrifying; his portrait of his great-grandfather sitting in a Kent kitchen reading Ovid’s poems of exile is heartbreaking.

De Waal writes that he was wary of his account becoming simply a collection of family anecdotes, of it appearing nostalgic, thin. ‘Melancholy, I think, is a sort of default vagueness, a get-out clause, a smothering lack of focus,’ he explains. ‘And this netsuke is a small, tough explosion of exactitude. It deserves this kind of exactitude in return.’

Aside from the gripping story of what happened to the netsuke when the Gestapo ransacked his family’s house, of how they were rescued and returned to their rightful owners, he wants to understand them in themselves; what it feels like to touch one of them, what they look like when they are arrayed in their vitrine, what each one of them communicates to the beholder.

But he also succeeds in setting off a similar chain of association in the reader. We do not have to own a collection of precious Japanese carvings to understand what he is talking about; most of us have an object in our possession that connects us to those we love and remember, that means something to us because of its physical presence and characteristics.

The Hare With Amber Eyes brings us a little closer to understanding why we form such attachments and the lasting value they can bring to our lives.

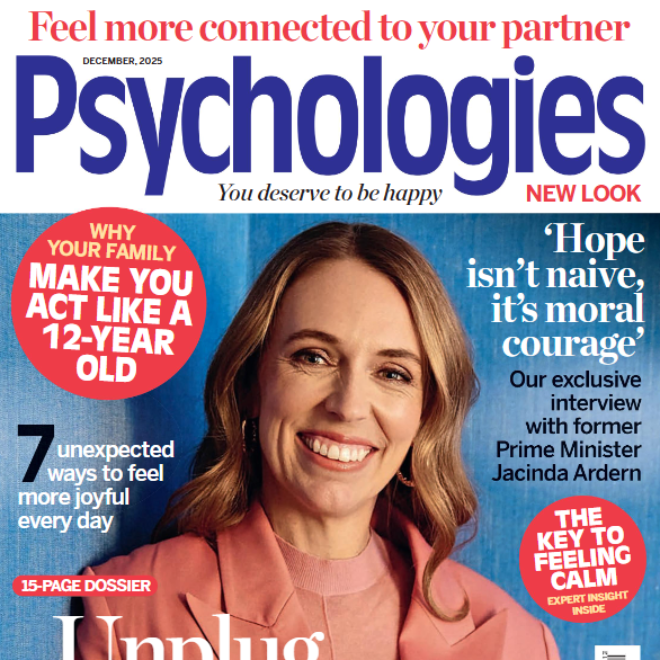

Photograph: Hannah James