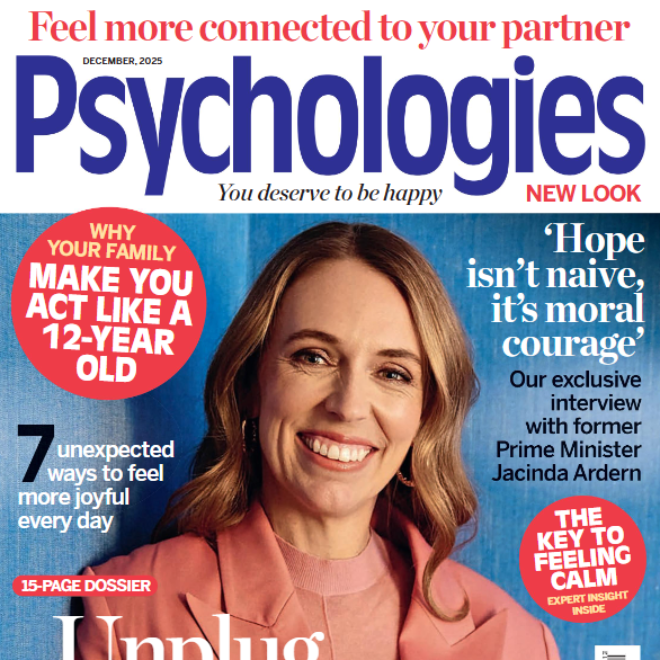

Gretchen Rubin: ‘It’s not seen as self-indulgent to pursue happiness now’

Gretchen Rubin explains why consistency, self-knowledge and better relationships are crucial for her own contentment

Gretchen Rubin explains why self-knowledge and better relationships are crucial for her own happiness and contentment

Words: Sally Saunders

When most of us take up a hobby, we might do it at the weekend, or perhaps every week or two. Not Gretchen Rubin. When the best-selling author of The Happiness Project starts a hobby, boy, does she start a hobby.

She’s visited the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York every day for more than five years (closures excepted), and now she has a new passion.

‘One of the things I’m doing in 2025 is I’m water colouring every single day,’ she tells me. ‘I’m kind of an all-or-nothing person, and so, for me, it’s easier to do something every day.’

It’s this single-mindedness, one could even say obsessiveness, while focusing on something so ephemeral as art, that makes Rubin so fascinating. On the surface she is, to use her own terms, a classic Upholder (Rubin created her Four Tendencies framework almost a decade ago, in which she categorises us based on our response to expectations, of which more later).

She has a ferocious intelligence: she went to Yale Law School and edited the Yale Law Journal before clerking for Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, and she’s gone on to teach at Yale Law.

But rather than follow this path further, perhaps making partner at a law firm, or becoming a judge herself, she has turned herself into one of the world’s leading researchers on the subject of happiness.

And, unsurprisingly, she’s not done it by halves. She blogs daily on the subject, sends out weekly newsletters religiously detailing five things that have made her happy that week, and has a weekly podcast.

Oh, and she’s written half a dozen best-selling books on the topic, that have sold millions of copies and have been translated into more than 30 languages.

So how can one be so laser focused on something so intangible as happiness? And does she feel pursuing this feeling so doggedly has helped her find it?

‘A lot of people have this idea that if you think about happiness too much, it’ll get in the way of your being happy,’ she says.

‘I myself do not see that. I do not see that people are spending too much time thinking about how to be happier. I think that by far the bigger thing is that you don’t think about it at all.

‘There’s this idea that thinking about happiness sort of trips you up. It’s something that rhetorically seems like it would make sense. But I don’t feel like it’s a problem that you actually see in the world that much.’

She does, though, believe that happiness is something we have become much more aware of in the last couple of decades, and for good reason.

‘There’s more acknowledgement that it’s worthwhile, and not self-indulgent to pursue happiness now,’ she says.

‘On the practical side, workplaces are more aware of the fact that happier people are more productive, more cooperative, more creative, have less burnout, less absenteeism.

‘And so I think there is kind of an awareness that we want people to be happy because we want them to be happy, and we also want them to be happy because they’ll be better at their jobs, or they’ll be healthier.

‘So I do think that there is a much more open discussion of how a person might be happier, healthier, more productive, more creative.’

And what has made the biggest difference to her own happiness?

‘Truly understanding that relationships are the core,’ she says, without a pause.

‘If, anytime, I’m trying to make a decision about how to spend my time, my energy, or my money, if it’s going to deepen or broaden my relationships, I always try to do it.

‘So do I go to a college reunion? Do I go to a newsletter conference? If a friend is saying, “Hey, do you want to get together?” I really make an effort to do all those things, because I know how important relationships are.’

Her second revelation harks back to her work on the ‘Four Tendencies’.

‘The other thing that has made most difference is just understanding how people are really very different from each other,’ she says.

‘When I started, I thought “Well, I’ll just figure out the best way to be happy, and the right way, the most efficient way for people to be happier, and then I’ll just convince everybody to do it, and then it’ll be problem solved.”

‘But no, you can’t do that, because Sally is so different from Gretchen, and the thing that worked for me, may be the very opposite of the thing that works for you.’

This is at the heart of her work on the Four Tendencies.

Her website explains them as Upholders, who respond readily to outer and inner expectations — keywords: ‘Discipline is my freedom’; Questioners, who question all expectations and meet them if they think it makes sense; essentially ‘I’ll comply — if you convince me why.’

Obligers meet outer expectations, but struggle to meet expectations they impose on themselves — ‘You can count on me; and I’m counting on you to count on me,’ while the rebel resists all expectations, outer and inner alike. Her motto is ‘You can’t make me, and neither can I.’

‘I feel like, in a way, knowing you’re a rebel is the highest value of all the tendencies, because I feel like rebels are the most misunderstood,’ says Rubin.

‘They’re the most different, and so much of conventional wisdom doesn’t work for rebels. For example, morning people will give you 50 reasons why working in the morning is sensible. But if you’re a night person, it doesn’t matter.

‘Everybody says making a to-do list is a good idea. Everybody says that something’s important to you, you should sign up for a class, right?

‘And so you might think that yourself, but if you’re a rebel, you might find that really, really hard. And then you’re like, “Well, what’s wrong with me?

‘Because if I put it on the to do list, I don’t want to do it. And if I sign up for a class, I don’t want to go. So maybe I’m not a real grown up, maybe I’m lazy. Maybe there’s something wrong with me.”

‘You’ve just assumed that everybody else is right, instead of understanding, no, that’s a tool that works really well for other people.’

It suddenly strikes me that these two terms in particular seem to have a lot in common with our current understanding about neurodiversity.

‘It’s very interesting, because people raise this to me all the time,’ she says.

‘It’s especially the case with ADHD, many, many people have asked me, “Do you see correlations? Is this sometimes the same thing?”

‘And I don’t know, I just don’t have big enough data, unfortunately. I would love for there to be a research project where they were really looking at that, it would be a really interesting way to go.’

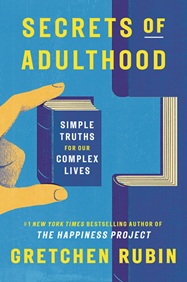

Instead of dipping her toes deeper into this area, her new work is focusing on what it does indeed mean to be ‘a real grown-up’.

‘It’s organised into the sort of things that we face in adulthood, like confronting the perplexities of relationships, getting things done, understanding the truth about ourselves, making decisions.

‘It’s the insights that I’ve had, that have come to me mostly through time and experience, all the little things I’ve learned.

‘The proverb is, “When the student is ready, the teacher appears”,’ she says.

‘And I do think that sometimes, you can read a single line and it’s like a giant light bulb goes off in your head, and you can see a situation more clearly or see the way forward.

‘I always push myself to write aphoristically, just partly for the creative fun of it, and also I think it’s more powerful as a way to communicate. So I’ve been amassing these for years.

‘And my my younger daughter was going up to college, so I thought, “OK, let me give you my secrets of adulthood. Let me, spare you some of my suffering.”’

What’s her favourite one liner?

Again, without pause, she says: ‘Accept yourself, and also expect more from yourself.’

She says: ‘This is very confusing to people, that both things are true, but sometimes, when you just see it written out like that, you’re like, “OK, I get it. I need to have self compassion, but I also need to put my push myself out of my comfort zone. But only I know where that is.”

‘That took me so long to understand that in my study of happiness, months and months. But it’s absolutely crucial.’

So where does she feel she is now, compared to when she began?

‘I just go deeper and deeper,’ she says. ‘There are always new things, always new areas. I feel like in The Happiness Project, I did a good job of laying out a foundation for figuring out how I think about it as a subject. And now I’m going to habits, deep, deep, deep into habits. Because if you study happiness, you quickly are led to habits.’

Which takes us back to her new daily habit of watercolours. Her reasoning for the intensity of her habit surprises me.

‘It’s easier for me to do something every day, because then, nothing matters,’ she says.

‘Like today, I did a really bad job. But do you know what? It doesn’t matter, because I’m going to be doing it again tomorrow.

‘There are lots of things I want to try, but I’m like, “I have so much time. I’ll get to that later.”

‘I’ve got plenty of time to explore that. I don’t have to rush.’

I suddenly see I’d got her all wrong. With her smartly-dressed petite frame and neatly coiffed hair, I thought she was all about perfection, and being perfectly happy.

But it’s the fact that her commitment and regularity actually allow her to feel calm and relaxed even when making mistakes, that actually leads to her happiness.

And I think that’s a secret we could all learn.

Secrets of Adulthood: Simple Truths for our Complex Lives by Gretchen Rubin (John Murray One, £12.99) is out now