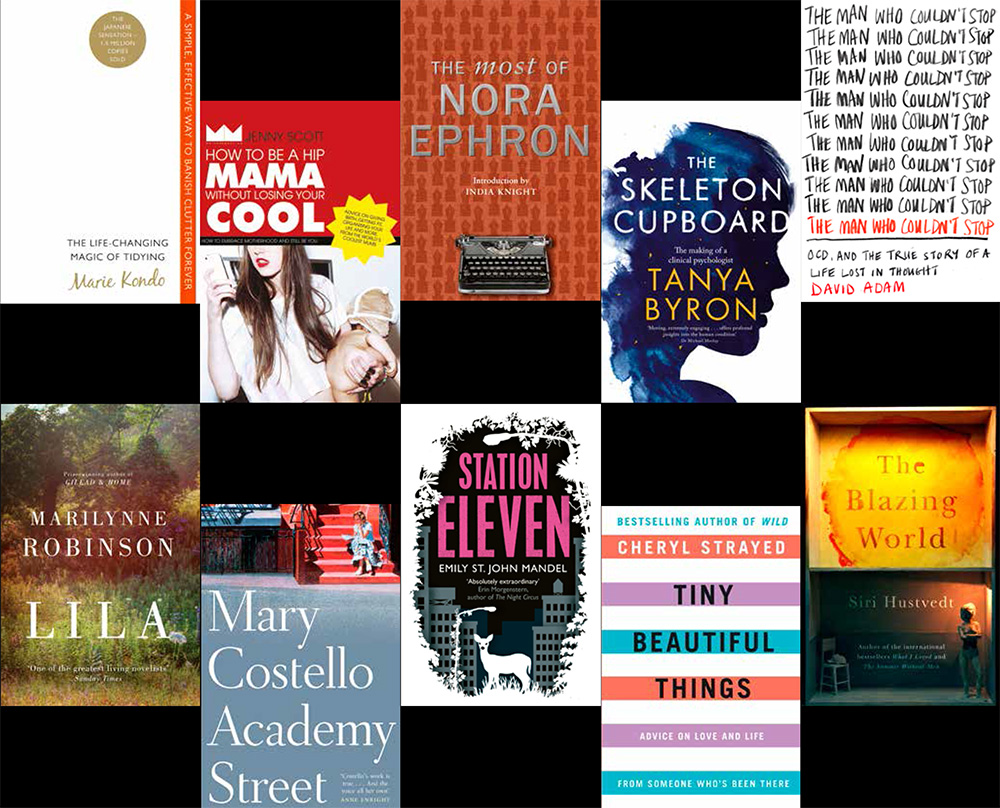

The Psychologies Books of the Year List

10 of our favourite books of the year

Mary Costello, Academy Street (Canongate, £12.99)

Costello’s first novel, recently shortlisted for the Costa First Novel Award, is a heartbreaking chronicle of the life of introverted Tess Lohan, born in rural Ireland in the 1940s where, as a young child, she loses her mother – a loss that seems to inform the rest of her existence. An emigrant to New York in her twenties, Tess lives a lonesome life of lost love and disappointed expectations. This could, as our reviewer Eithne Farry pointed out, ‘have been thin fare in another writer’s hands. But Costello’s prose is lit from within, recounting Tess’s fierce but repressed passions, with such rapturous yearning that you are completely invested in her vibrant inner world. You will find yourself holding out hope that she can grasp hold of her life and change it for the better.’

READ IT: For a devastatingly sad, unsentimental and beautifully wrought account of a quiet life.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘Another vocation, then, reading, akin, even, the falling in love, she thought, stirring, as it did, the kind of emotions and extreme feelings she desired, feelings of innocence and longing that returned her to those vaguely perfect states she had experienced as a child.’

Cheryl Strayed, Tiny Beautiful Things: Advice on Love and Life from Dear Sugar (Atlantic, £8.99)

When everyone has seen Wild, the film (out January 16 in the UK and Ireland) and rushed to read Wild, the book, and then felt the loss of Cheryl Strayed’s wise, comforting voice in their lives, they’re going to need somewhere to turn. There’s her first novel, Torch, but if you want to get a straight shot of the hard-learned wisdom on display in Wild, head straight to this collection of her very alternative, often poetic advice columns under her alter ego, ‘Sugar’. They are particularly suited to those who think they don’t need advice columns, or that agony aunts are smug, finger-wagging know-it-alls with no insight into real lives. Remember, Cheryl has been there. You name it – a death in the family, drug abuse, infidelity, work struggles – she’s had it thrown at her or thrown it at herself. It’s taught her how to live, how to be truly authentic – an over-used concept these days but one that Cheryl owns. Learn from even one of the columns in here, and you’re on your way to being a better human.

READ IT: To grow stronger, wiser, better and brighter.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘Forgiveness doesn’t sit there like a pretty boy in a bar. Forgiveness is the old fat guy you have to haul up a hill.’

Jenny Scott, How to Be a Hip Mama Without Losing Your Cool (Hardie Grant, £12.99)

The subtitle of this book says it all – ‘how to embrace motherhood and still be you’. As a mixed team of mothers and non-mothers at Psychologies, we know just how much fuss, guff and generalised panic there is out there about pregnancy, motherhood and parenting. Rules and regulations seem to arrive from on high on from the moment you find out you’ve conceived and continue through your child’s journey towards adulthood. The effect on your own identity once your child is born can be enormous. So we loved this book for its lighthearted, reassuring and practical suggestions (because none of us needs any more ‘advice’) from a host of mums who are also still proud to be people.

As author Jenny Scott, founder of events business Mothers Meeting, explains, ‘[I wanted] to create a place where I could still be myself, where I could still have interests in art, design, music and fashion and be a mum. I didn’t want to lose my personal identity just because I’d given birth’.

PS: Some of the suggestions, particularly a brilliant list entitled ‘how to get sh*t done’, are equally useful for the child-free.

READ IT: To remind yourself that just because you’re having a baby, you don’t have to go gaga.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘Try and recognise when you’re being neurotic and laugh at yourself. It’s human nature to imagine the worst, but the likelihood of a runaway elephant trampling down your baby while in the nursery is very small.’

Nora Ephron, The Most of Nora Ephron (Doubleday, £20)

Ah, Nora, how we miss you but, oh, how your words – many of your sparkling words – live on brilliantly in this, your almost-collected works. This 416-page collection was part-arranged by Ephron herself a few years before she died in 2012, and brings together everything from Ephron’s most famous screenplay, When Harry Met Sally, to her various columns for Esquire. We particularly loved the ‘Crazy Salad’ columns, and the introduction by another of our favourite columnists, India Knight.

READ IT: To see that even when dreadful things are happening to you, there’s always the opportunity to turn it into a funny story…

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘Above all, be the heroine of your own life, not the victim.’

Siri Hustvedt, The Blazing World (Sceptre, £8.99)

If you’ve read any of Hustvedt’s novels or non-fiction before, you’ll know that hers is a blazing mind, with ideas that spill from every page. In this her latest novel, she creates the magnificent Harriet Burden, a rejected, angry artist with ‘ideas dancing in her head like fireflies’. Deciding to play a gigantic trick on the art world, she uses male artists as a front for her work to prove a point about gender bias, a plan that is set to put her in serious danger. Filled to the brim with snatches of psychoanalysis, neuroscience and philosophy and full of ambiguities, this is a complex mystery novel with a difference – told after Harriet’s death, from the perspective of both friends and enemies.

READ IT: To find yourself challenged and then rewarded.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘We project our feelings onto other people, but there is always a dynamic that creates those inventions. The fantasies are made between people, and the ideas about those people live inside us … And, even after they die, they are still there. I am made of the dead.’

David Adam, The Man Who Couldn’t Stop (Picador, £16.99)

We assess teetering piles of books about psychological ‘problems’ every year but very few achieve just the right mix we’re looking for – scientifically rigorous, but with emotional depth and understanding and a lightness of touch that avoids pontification or pretentiousness. Adam, an editor for science journal Nature, hit the ball out of the park this year with this personal account of his own experiences of a commonly misunderstood condition, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Whether you’re just intrigued by this famous disorder or whether you or someone you know has endured it, this is a must-read.

READ IT: To understand why OCD is not about straight lines and handwashing, but about our struggles with something common to many of us – ‘intrusive thoughts’

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘People who live with OCD drag a metal sea anchor around. Obsession is a break, a source of drag, not a badge of creativity, a mark of genius or an inconvenient side effect of some greater function.’

Marilynne Robinson, Lila (Virago, £16.99)

At first glance, Lila isn’t the obvious ‘starter’ novel you might approach an author with, given it’s the third in a series centred around the imaginary town of Gilead in Iowa in the first half of the 20th century. But you can jump right into it without having read the others, which is exactly what we did. Robinson is a quiet writer; she takes you by stealth. Main character Lila has taken a long, difficult journey before she arrives at Gilead, marries the local preacher and gains a security she’s never enjoyed before. So begins an internal debate about the virtues of staying versus the dangerous freedom of that long road. That’s pretty much the bones of story, but the way that Robinson makes you live the days with Lila… well. You are given the grace to encounter the mysterious life and thoughts of another human in the space of 260 pages.

READ IT: Slowly, in a quiet space, to savour the rich world Robinson creates with seemingly simple ingredients, and to think about the big questions her characters pose about how to live.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘It has taken me a very long time, a very long time, to give myself permission to fly and breathe fire.’

Marie Kondu, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying (Vermilion, £10.99)

This book is going to offer a major challenge to anyone who struggles with clutter, but if you’re fighting against bulging wardrobes and tripping up over time-saving gadgets, it could be your saving grace. Kondu goes against all the received wisdom about tidying (e.g. spending 15 minutes a day on a drawer) and mercilessly instructs you to begin now and to do all of it at once. Only then, she warns, will you get a real sense of just how much stuff you’re hoarding. If you find yourself bristling at her advice, it might be time to search your conscience (or the famous third drawer down) – Kondu goes deep and asks you to examine what exactly your messiness means. As our special section on decluttering in our January 2015 issue points out, this generation has up to six times as many possessions than the generation before us. We have to at least ask ourselves the question as to whether it’s making us any happier. And Kondu won’t only help you get rid of what you don’t need, she’ll give you tips on how to make sure you don’t revert to old habits. Overall, slightly nutty, but guaranteed to free up some breathing space.

READ IT: Then pass it on (Kondu advises you not to allow her book to become yet more clutter).

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘I came to the conclusion that the best way to choose what to keep and what to throw away is to take each item in one’s hand and ask: “Does this spark joy?” If it does, keep it. If not, throw it out.’

Emily St John Mandel, Station Eleven (Picador, £12.99)

We raved about this one when it first came out back in September and since then it has been shortlisted for a National Book Award in the US and been slowly burning its way in the the consciousness of end-of-year reviewers. Please don’t miss out on what has to be the best apocalypse novel to arrive on the scene in some time.

The survivors of a deadly strain of flu virus exist in ‘Year Twenty’ of a world where over 99 per cent of the population has been annihilated, leaving those unhappy few left behind as wanderers, lost on the huge continent of North America – made even more giant by the grounding of planes and the quick pointlessness of cars, abandoned as gas runs out. With the loss of electricity, there is no web, no phones, no modern printing presses. News travels on foot from town to town.

What a really great apocalypse novel does is make you appreciate everything you take for granted. Mandel’s writing reminds you of the beauty of the world you’re living in right now. What if you knew you might never eat an orange again? What would it be like to press a light switch and not have the light come on? Odd once – but to have it happen over and over again? And in a world where we regularly live or travel far from our loved ones and community, just how are we supposed to stay in touch without the help of satellites?

The ragtag band of musicians and actors who lead us through this new existence are torn between homesick longing for the world they remember and a driven compulsion to just keep walking, to keep on keeping on. But they want to be more than mere survivors of a lost world – using a mixture of Shakespeare and classical music, they try to bring a little bit of art back to a world sadly lacking in glamour. But the end of the world brings End of Days prophets and when one such crosses their path, the focus returns to simple survival.

Mandel weaves a complicated but beautiful web as she flips us between the pre-flu world and the one our characters are stuck in now, taking in themes like the weirdness of celebrity and fame, how we change over time, alternative families and – more than anything – what loss means and how we humans cope with it.

READ IT: For a loving rendition of a world made both beautiful and terrible by the near disappearance of Homo Sapiens.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘Jeevan found himself thinking about how human the city is, how human everything is. We bemoaned the impersonality of the modern world, but that was a lie, it seemed to him; it had never been impersonal at all. There had always been a massive delicate infrastructure of people, all of them working unnoticed around us, and when people stop going to work, the entire operation grinds to a halt. No one delivers fuel to the gas stations or the airports. Cars are stranded. Airplanes cannot fly. Trucks remain at their points of origin. Food never reaches the cities; grocery stores close. Businesses are locked and then looted. No one comes to work at the power plants or the substations, no one removes fallen trees from electrical lines. Jeevan was standing by the window when the lights went out.’

Tanya Byron, The Skeleton Cupboard: The Making Of A Clinical Psychologist (Macmillan, £18.99)

Psychologies columnist Sally Brampton sums up the core appeal of Byron’s memoir well: ‘Quite simply, I love this book for its candour, wisdom and courage. Mistakes are our greatest lessons and other people, wherever we find them, our greatest teachers … Life is about connection. There is nothing else.’ An account of Byron’s early days learning how to practise as a psychologist (using stories based on some of her patients but altered to preserve anonymity), it’s an honest, revealing and encouraging reminder of how human a skill psychology is.

READ IT: To see through diagnoses and labels to the humanity of both psychologist and patient.

FAVOURITE QUOTE: ‘I’ve always wanted to challenge the stereotypes of those with mental health difficulties, to destigmatise vulnerable people struggling with the weight of their own distress and the fear they are unable to cope with life … Revealing my own fears and inadequacies when trying to help anyone with a mental health problem felt like an important part of that.’