October Shelf Help: Alex Clark on Stoner

Alex Clark on the quiet success story that is John Williams' Stoner

What is it, wondered Bryan Woolley in a 1986 interview with John Williams for the Denver Quarterly – the literary magazine attached to the University of Denver, at which Williams taught for over 30 years – that makes his books so strikingly different from one another, to the extent that one could believe them the work of different writers? There is his darkly psychological debut novel, 1948’s Nothing But The Night, from which he was to distance himself in later life; his second, Butcher’s Crossing (1960), a novel that might have had a Western setting but was distinct from that genre; 1965’s Stoner; and his final novel, Augustus (1972), a retelling of the life of the Roman emperor in epistolary form. What a mixed bag! But perhaps, suggested Woolley, what unified these works was ‘simply the belief that although a civilized person maybe whipped by the world, he doesn’t have to be defeated by it’.

That description serves very well as a way of viewing Stoner, a novel that was neither unduly ignored nor unduly celebrated during its author’s lifetime, but which has enjoyed a remarkable second life in recent times. It is, in precis, fairly unpromising material: the story of a man, William Stoner, who attends the University of Missouri as a teenager, thereafter becomes a teacher at the same institution, marries not very happily and, eventually, dies. And yet, as both its very high-profile fans – such as the late John McGahern, who introduces this Vintage edition, Ian McEwan and Julian Barnes – and the legions of readers who have discovered it over the last year or so will know, its sparse and apparently undramatic storyline is deceptive; for in its pages, it reveals a human life in its entirety, from its epiphanies to its longueurs, from delight to desperation. It is, in parts, an undoubtedly sad book; but as Julian Barnes pointed out in a piece written for The Guardian, its sadness ‘is of its own particular kind. It is not, say, the operatic sadness of The Good Soldier, or the grindingly sociological sadness of New Grub Street. It feels a purer, less literary kind, closer to life’s true sadness’.

And during the course of novel we begin to appreciate what might be meant by ‘a civilized person’. It is not, certainly, a question of class or wealth. Despite the fact that Stoner, whose parents are farmers and who initially goes to university to study agriculture, leaves his rural background behind him, the trajectory of his life is not a matter of social mobility or the acquisition of material goods. Rather, it is a question of his response to what happens to him as he sits in a classroom and encounters, for the first time, a Shakespeare sonnet. His reaction is so profound and so all-encompassing that he experiences it at a physical level:

‘William Stoner realized that for several moments he had been holding his breath. He expelled it gently, minutely aware of his clothing moving upon his body as his breath went out of his lungs… He turned his hands about under his gaze, marvelling at their brownness, at the intricate way the nails fit into his blunt finger-ends; he thought he could feel the blood flowing invisibly through the tiny veins and arteries, throbbing delicately and precariously from his fingertips through his body.’

This life-changing moment happens only a few pages into the novel, and all the rest of the action – such as it is – can be said to proceed from it. And for all the many reverses that Stoner suffers during his lifetime, both professional and emotional, in this respect he is lucky; his vocation, and the course of his life, is set early, and all he needs to do is to hold firm to it. But it is this steadfastness, this belief in the significance of literature and in his duty to help his students to apprehend it, which may have led Williams, in that Denver Quarterly interview, to describe his creation as ‘a real hero’.

In that conversation, Williams also discussed his fears about the future of education, about what might happen to it in the hands of those who are ‘deathly afraid of that which they don’t understand’. Stoner, both the character and the novel, are the opposite; they stare intently at whatever might seem to resist immediate understanding until it begins to take shape.

Quite apart from the readerly satisfaction offered by this powerful and resonant novel, the ‘rediscovery’ of Stoner is also cheering for other reasons. It reminds us that literature is not simply a matter of new releases or of classics that we already know well, of books that we see extracted in newspapers or advertised on trains or adapted for television. It is also a vast landscape, spreading across countries and continents and back in time; a place so populous and varied that we will never be able to visit all of it. But we can stumble across hidden corners and find stories that we didn’t even know existed and be rewarded by an exciting new discovery; and, in the process, remind ourselves that the world of books is a constantly shifting, constantly renewable source of inspiration and pleasure.

Stoner by John Williams is published by Vintage at £8.99, ebook available. You can find out more about the Shelf Help list by clicking here: http://www.vintage-books.co.uk/books/shelfhelp/

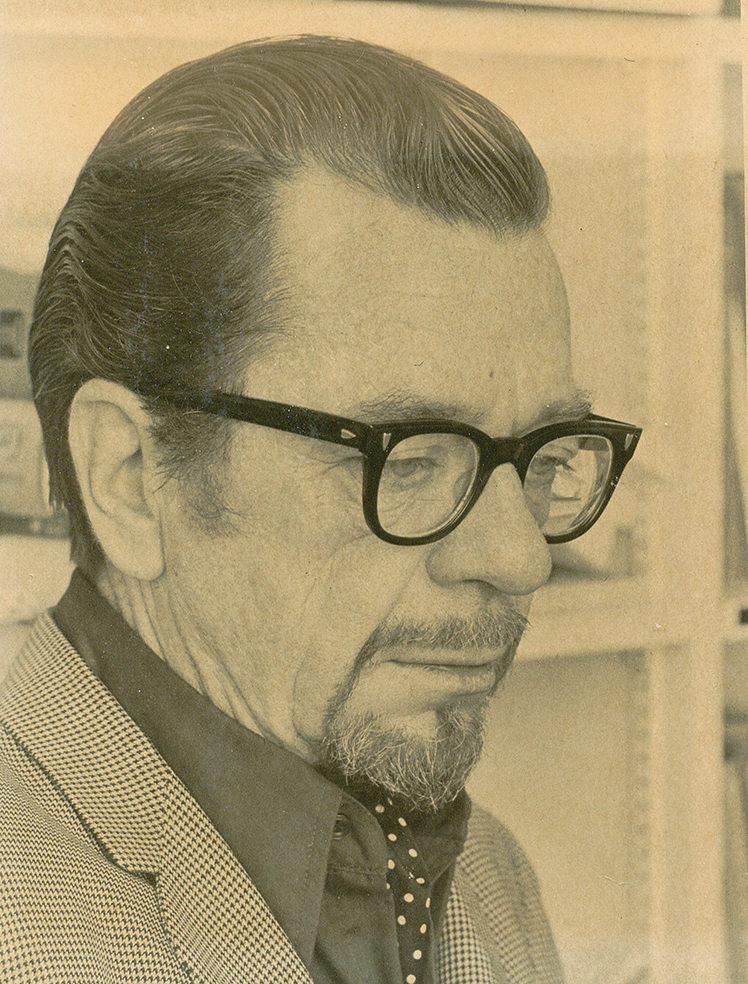

Photograph: The University of Denver