How to answer life’s big questions

Felicia Jackson from children's book publisher Rapscallion Press focuses on answering young children's big questions about life, the universe and everything, while author Virginia McLean talks about her inspiration for her book, Journey To The Beginning Of The World

Society is built on ideas about who we are and the values we share. Often the beliefs and values shared by a society are transmitted through storytelling, which has been fundamental to the transmission of knowledge and information throughout history. Given recent political upheaval and the increasing complexity of the world however, we need to ask: what kinds of stories are being told, who tells them and why are they telling them?

If we want to raise a generation of open-minded and flexible thinkers, children need to understand the importance of these questions – and we need to start as young as possible. Whether you have a child yourself, or have been watching Gogglesprogs, you know that children’s questions and their view of the world are often highly insightful.

The psychologist Vygotsky believed that while there may be skills and ideas that children find too difficult to master on their own (particularly at an early age) discussion, guidance and interaction with others provides the ‘scaffolding’ which enables a greater development in thought. That suggests that young children have the capacity to explore and understand incredibly complex ideas.

Kiki Mastroyannopoulou, consultant child psychologist at Norwich University Hospital agrees saying, “Children playing with ideas and having conversations about complex philosophical concepts through a collaborative process, is therefore going to lead to jointly created ideas and possibilities that a child alone may find it hard to generate or grasp. If an adult is part of this collaborative conversation, then that provides the scaffolding necessary to make sense of concepts that may otherwise be beyond the grasp of younger children.”

Luckily a process exists that uses this approach – the practice of philosophy for children (P4C). Peter Worley, philosophy facilitator and chief executive of the Philosophy Foundation, a charity that aims to bring high-quality philosophy into schools by training philosophy graduates, believes that children have a natural understanding of philosophy simply because of their own lives. Philosophy matters to children, says Worley, because they come across these questions all the time – “I experience myself as me, but what does that mean as I change? Am I still me?”

Angie Hobbs, Professor of the Public Understanding of Philosophy at the University of Sheffield says, “Philosophy can help children have the courage to ask why something has authority, or why someone is right. This in turn helps protect them from indoctrination. Philosophy is about giving people the tools to run their own lives.”

Maria Prodromou, philosophy facilitator and SAPERE trainer, sees the benefits in the everyday. She says, “Philosophy has a huge impact on children’s emotional wellbeing and confidence. It creates a safe and caring environment for children to speak their minds and feel that they will be listened to.”

In a world where there is fear and an awareness of its complexities, we need to help our children find ways of facing challenges. At Rapscallion Press, we believe that storytelling and philosophy are the best ways for children to learn about and understand their world. What’s most important are stories with gaps enabling children to fill in the blanks – stories that stimulate their thinking.

Rapscallion Press is an independent children’s book publisher focused on philosophy and critical thinking through storytelling. We also run workshops on subjects from religious tolerance to maths and physics using a philosophical approach. As part of our mission we operate a foundation called Learn to Think dedicated to encouraging a generation of flexible and open-minded thinkers: essential in developing a culture of global tolerance.

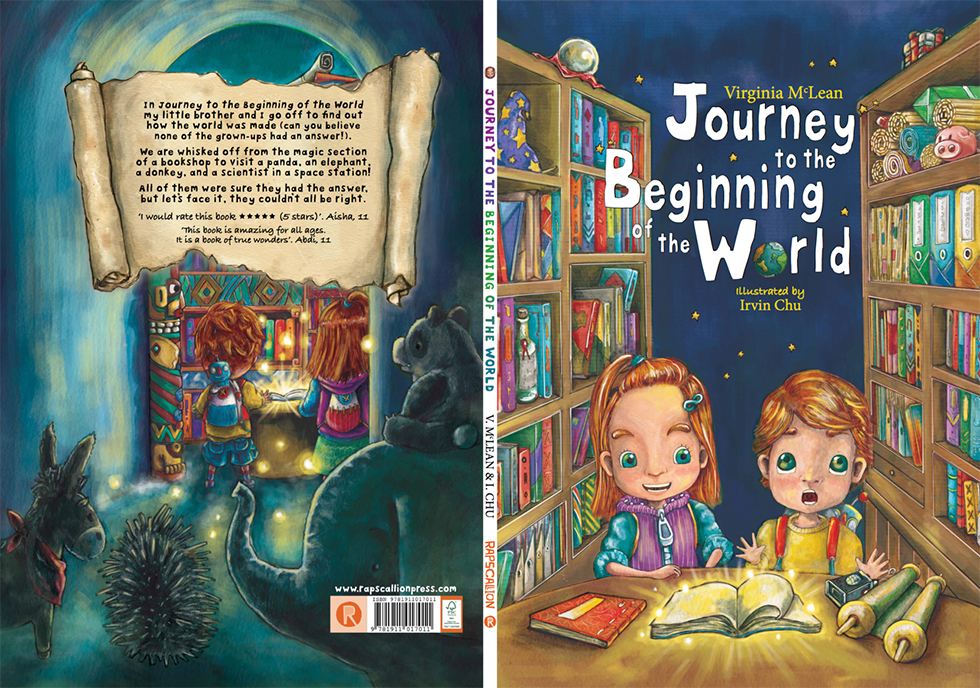

We talk to Virginia McLean, author of Journey To The Beginning Of The World (Rapscallion Press, £7.99), about her inspiration behind the book

You say the book was inspired from trying to answer your children’s question of “how was the world made?” How did you even begin to try and include everything, while still keeping it simple and accessible?

Yes, it was my daughter who went through a phase of asking me these really big, hard questions: Does a dog dream? Why are people mean? What is God? Are there aliens? Asking around, I realised it was something most children do. I had no idea that young children’s minds were so busy with profound conceptual thinking, asking the questions that are engaging the academic scholars of philosophy!

Believing in encouraging my child’s curiosity and wanting to be able to provide wonderful explanations, I found myself struggling to do these questions justice. I hunted for the book that I knew must be around somewhere, as all children were asking such questions, but all I could find were religious books or science text books. So I set about trying to write her an overview of possible answers in the form of storybooks. They needed to be fun, or it would be just a boring text book.

I decided to start at the beginning with creation. But what to include? There are so many thousands of creation stories, then even more versions of the story within the same religion or traditions. It was after many hours of cafe time, combining my PR skill of simple message delivery with academic research and evidence building, that I decided to try and cluster together the main current beliefs – Chinese, Abrahamic, Hindu and scientific.

I realised that a focus on detail and comprehensive coverage were not going to help. I could never include everything nor get the versions ‘right’ enough to keep everybody happy. It was more important to me to capture the essence of the stories and convey the many answers which have been provided by faith and science, from many different times and many different places.

How did you go about forming a concept for the book? Did it take many attempts or did you have a vision of the characters visiting a magical library and having time-travelling adventures?

That bit was much easier. I regularly visited my local library as a child, so stacks of books have an important place in my early imagination. The magical bookshop is actually modelled on my local bookshop, Primrose Hill Books, and even though the illustrator had never been there or even seen pictures, when the owners saw the image they said, “that’s our bookshop!”

The time-travelling idea came from the realisation that, despite having just finished a Masters in Chinese Studies, I had no clue what almost 20% of the world’s population were brought up with as their creation story. Even now, I have adult readers telling me they had never heard of the giant Pangu! I wanted my kids to be outward-looking and curious about other people, to seek views from all over the world and not just from their own back yard.

Some of the most encouraging moments are when we visit schools and children tell us that they didn’t know before that there was more than one belief system, and that it wasn’t unusual for different people to believe different things.

Why did you go for 5 different illustrators, instead of just one? How did you co-ordinate it all?!

What we wanted was to make a book that would be treasured, that never got dull, that warranted re-examining as many times as possible. It had to be rich in detail and layers of interest. We also wanted to show as many perspectives as possible and appeal to children who are more visual. Just because they can now read, doesn’t mean they don’t like pictures any more.

Irvin Chu, the main illustrator, is young, male, thinks in pictures, and is Hong Kong Chinese – so offers a completely alternate perspective to mine. The other works were images of creation either donated or created for us by five artists. The co-ordination of so many people is a challenge and makes the project longer, but we want to make books that are really different and that we can be really proud of.

We also do all our projects as collaborations. Although I was the author of this book, it soon developed a life beyond me as my partners in Rapscallion Press got involved. With our latest titles we work as a team of content developers working with experts in different fields like Physics and Maths.

It’s clever how you invented the baby animals to travel with the children, representing the different beliefs, all of whom believe they are right and also the ‘hall of mirrors’ concept at the end. What inspired those interpretations?

It was my daughter’s idea to have cute animals on her adventure – the wise old animals and the babies. It also became clear that this was a clever way to avoid saying, “this is what Chinese people think”, or “this is what Hindus believe”, because of course it’s not as simple as that. It is a clue to the origin, without being definitive.

The conclusion was the hardest bit. How to convey the idea that there are many versions of an answer, that none of them are necessarily ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, that they are believed to be right by the people that hold them, that your answer is often influenced by where you come from… It was a minefield! But I remember being told as a child that reality is made up from shards of truth, and that gave me the idea for the hall of mirrors. It helped convey that idea that we only see partial truth, it’s affected by where we stand, and that it is hard to actually see reality.

Can you tell us a bit about the next book in the series?

The next book, Journey to the Afterlife, goes straight to perhaps the most difficult and unwanted question a child can ask – ‘what happens to us after we die?’ My daughter’s headmistress told me about a child whose relative “went to sleep and never woke up”, leaving the child with sleep phobia, and a family who asked for the school not to celebrate Mother’s Day, for the child who had lost her mother.

I think it’s so important to be honest with children – not to fob them off or tell them well-meaning but damaging fictions; to find out about what the rest of the world believes about the afterlife and marvel at this wonderful unknown.

For more information about Rapscallion Press, click here

Photograph: iStock